Philadelphia’s Fairmount Water Works was a monumental undertaking, the first structure of its kind and scale in the city. Designed in 1811 and built over three years, it served as Philadelphia’s primary drinking water source until 1909. Beyond its vital function, the area surrounding the Water Works quickly became a beloved recreational spot for city residents. Learn more at philadelphia.name.

In 1976, the Fairmount Water Works was designated a National Historic Landmark. Interestingly, it was here that special water wheels were used for the first time in U.S. history to move water. After its closure, the former station was transformed, housing a restaurant and a museum. We’ll delve deeper into the past and present of this remarkable place in this article.

Fairmount Water Works: The Beginning

The first water pumping station in Philadelphia was constructed in 1799 at Centre Square, where City Hall now stands. Steam engines pumped fresh water from the Schuylkill River to the pumping station, which then distributed it through city pipes. However, Philadelphia was growing rapidly, and the plant simply couldn’t keep up. Its engines constantly broke down, and the reservoirs were too small. This quickly highlighted the need for a new water supply station.

In 1811, young engineer Frederick Graff, who managed the old plant, proposed building a new facility in Fairmount, right next to the Schuylkill River. He designed reservoirs atop a hill, planning to pump water there, allowing gravity to then distribute it through the city’s pipes. The Water Committee approved his project, and construction began that same year.

The first structure erected was the engine house, housing two steam engines, pumps, and boilers to lift water from the river. Its exterior resembled a country villa, situated in an exceptionally picturesque location. Three years later, construction was complete, and the new water supply station was put into operation.

It immediately and significantly increased the city’s water supply, but also dramatically raised its operating costs. By 1819, the annual cost of running each engine was estimated at $31,000, factoring in wood for fuel and maintenance. Graff then proposed building a weir (dam) across the river, allowing the pumps to operate using the power of flowing water.

Construction on the new dam began in 1819 and lasted two years. The completed dam became the longest in North America at the time, stretching 2,008 feet. A mill was built on the riverbank, with a channel dug behind it to direct water to turn the water wheels, with any excess returning to the river. The dam made the water supply station’s operation far more efficient. From then on, it not only stopped being a financial drain but actually began generating profits. For instance, in 1844, the Fairmount Water Works supplied approximately 5.3 million gallons of water daily to 28,082 customers at a cost of $29,713, while the city treasury netted $151,501.

More Than Just a Water Station

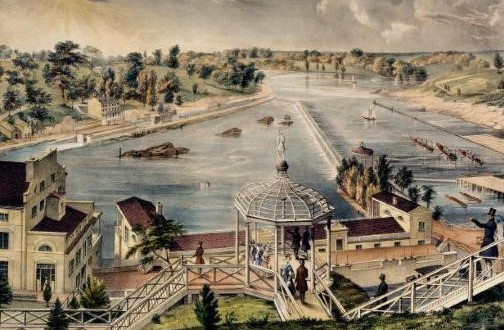

Thanks to Frederick Graff’s ingenuity, his project became not just a crucial piece of infrastructure but also transformed into a popular riverside retreat. He designed two administrative buildings on the mill terrace in the style of classical temples. A pedestrian bridge led to them, offering visitors a chance to stroll and enjoy the roar of the water. An observation pavilion overlooking the Schuylkill River was also built atop the station.

Further modernization and beautification efforts were undertaken, including:

- The former quarry beneath the engine house was transformed into the South Garden between 1829 and 1835.

- An elegant gazebo was built at the eastern end of the spillway.

- When the old steam engines were no longer in use, the engine room was converted into a salon.

- The riverbank was developed for the convenience of city residents.

Thus, the creator of this place managed to combine the beauty of nature with the wonders of human ingenuity and resourcefulness.

In 1845, the city purchased the former estate of Robert Morris, located west of Fairmount. It was combined with the area around the station to create a public park.

Further Development and Closure

Meanwhile, Philadelphia continued to expand, and its population grew. To increase the volume of available water, a new hydraulic turbine was installed at the station. New reservoirs were created on Corinthian Avenue, and in 1859, a new mill with three turbines was built. Its roof also became an observation deck for visitors.

From 1868 to 1872, the old mill was rebuilt to accommodate three new turbines. The work was overseen by the chief engineer of the city’s water department, Frederick Graff Jr., who drew upon his father’s designs to create a columned pavilion on the terrace and several new structures. Timely renovation, much like with the Frankford Avenue Bridge, extended the lifespan of these structures.

For another two decades, the station continued to benefit the city. However, due to industrialization along the Schuylkill River, its waters became heavily polluted by the late 19th century. In 1890, Philadelphia experienced outbreaks of cholera and typhoid fever. The Fairmount Water Works did not treat drinking water, unlike newer water supply facilities that had begun to do so. This ultimately led to its closure in 1909.

A Place for Recreation and Entertainment

In 1911, the mills of the Fairmount Water Works were converted into aquariums. Initially quite popular, their visitation significantly declined after World War II. Subsequently, a swimming pool was built in their place. Ten years later, Hurricane Agnes flooded it, and the premises of the former water supply station remained defunct for the next two decades.

In 1974, the Junior League began fundraising for its restoration, even allocating $24,000 for weather protection. Government officials took notice of the site. In 1976, this location was designated a National Historic Landmark.

By 1988, $23 million had been raised for the restoration of the structures. With these funds:

- A practical science and environmental education center was created in the old mill building.

- The engine room was transformed into a restaurant.

- The South Garden was restored to its original state.

- Even the pavilion for accessing the top of the former waterworks structures was rehabilitated!

The site began hosting interactive exhibits, lectures, and various events for both adults and young visitors. As a result, this location quickly regained its former popularity, attracting numerous visitors eager to explore its history and admire the surrounding natural beauty.

It also caught the attention of business owners. In 2004, Michael Karloutsos won a 25-year lease for $120,000 annually. He undertook renovations and opened the “Water Works” restaurant and lounge in 2006. However, it closed in 2015. Instead, the venue was re-equipped to host a variety of events.

For over two centuries, the Fairmount Water Works provided Philadelphia with two crucial, yet distinct, services. Its initial mission was to supply water and meet the needs of a rapidly growing population. At the time, this project was innovative and proved to be a complete success. Regarding its second role, the exquisite design and its location by the Schuylkill River led to the creation of North America’s largest landscaped urban park and a network of educational and recreational offerings for city residents.