The story of the first fully functional electronic digital computer, ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer), is intimately tied to Philadelphia. It was here, within the walls of the University of Pennsylvania’s Moore School of Electrical Engineering, at the height of a world conflict, that the machine that would change the world was born. The invention, officially unveiled in February 1946, served as the technological bridge between the mechanical era and the world of digital technology. Further on the website philadelphia.name.

The Military Demand

The primary and undeniable impetus for creating this colossal device (ENIAC) was the U.S. Army’s urgent need for ballistic calculations. This requirement was directly driven by the dynamics of World War II.

During the war, artillery units were constantly receiving new types of guns and shells, for which it was vital to quickly generate firing tables. Each calculation of a shell’s trajectory was extremely labor-intensive, requiring approximately a thousand mathematical operations.

This work was performed by people—mostly female mathematicians—who were then called “computers” (calculators). Calculating just one trajectory took a skilled human “computer” about 16 days. In the dynamic conditions of wartime, where time was measured in lives, such a speed was critically insufficient and unacceptable. The army was drastically falling behind in providing the front lines with up-to-date data.

This backlog created a top-priority military problem. The Army sought a tool capable of operating significantly faster and more accurately than human resources. The need to replace weeks of tedious computations with mere minutes became the key financial and intellectual catalyst that pushed engineers at the University of Pennsylvania to begin work on the first electronic digital computer. In fact, the strategic necessity of winning the war sparked the digital age.

The Founders of the Computer Era

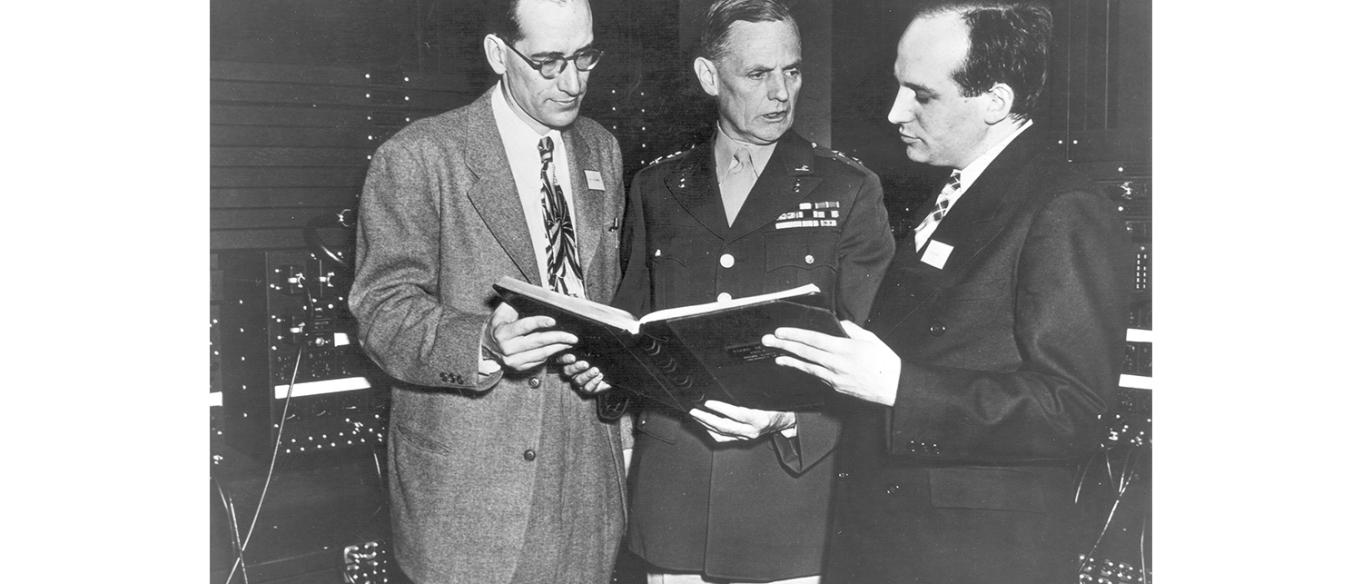

The project was spearheaded by two talented engineers: John Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert. Mauchly, a physicist by training, proposed the revolutionary idea of using vacuum tubes instead of slow electromechanical relays. Eckert, serving as the chief engineer, ensured the technical realization of this concept.

Work on ENIAC began in 1943 under strict secrecy. The machine’s construction required about 200,000 man-hours and nearly half a million dollars—a colossal allocation of resources for that time.

Staggering Specifications

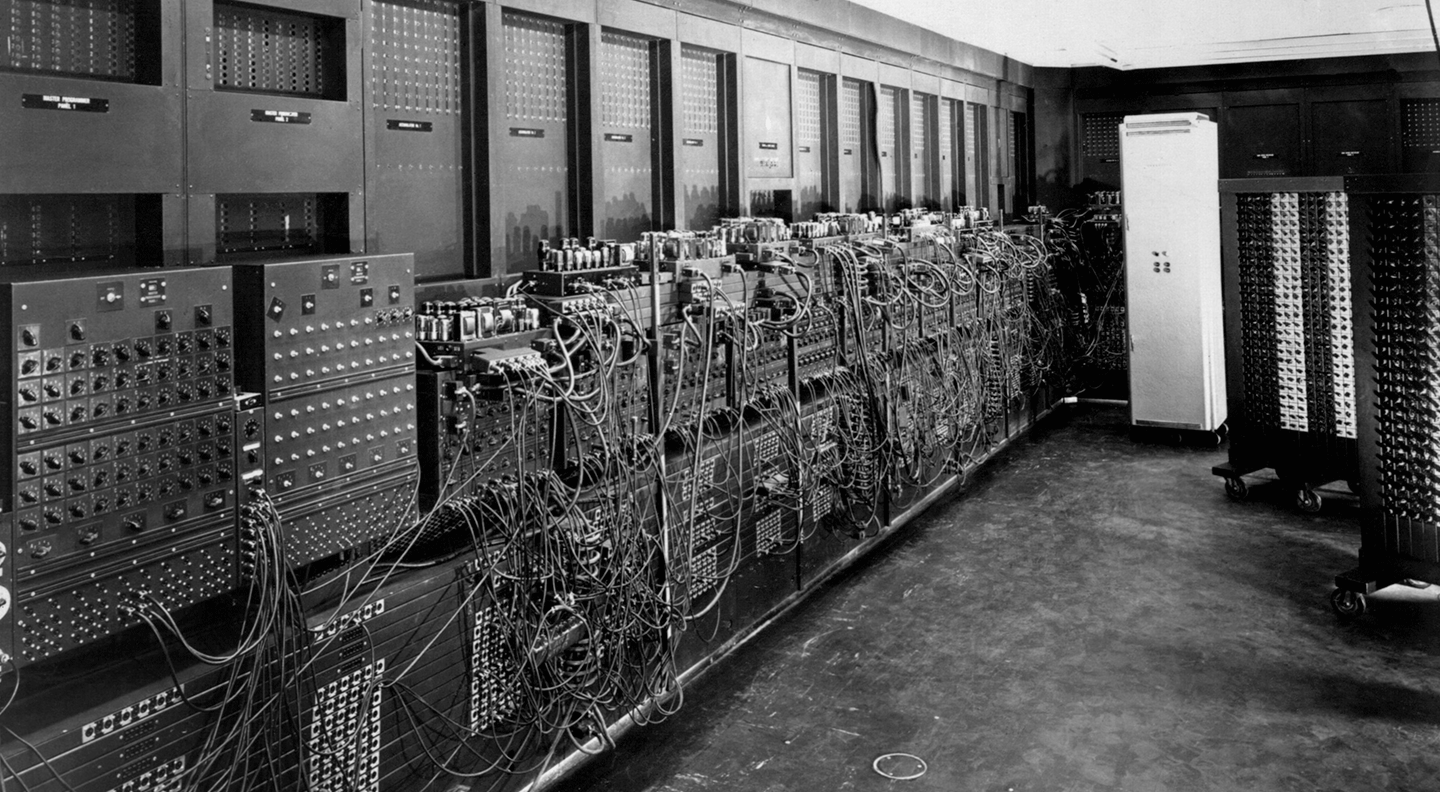

ENIAC’s characteristics were astounding. It occupied an area of 1,800 square feet (1.67 a), weighed 30 tons, and consisted of 17,468 vacuum tubes of 16 different types, along with thousands of resistors and capacitors. Its power consumption reached 150 kilowatts, necessitating the installation of a dedicated air conditioning system to prevent overheating.

Despite its massive size, its computational power was phenomenal. The computer could perform up to 5,000 additions or 357 multiplications per second, outperforming its predecessors by a thousandfold.

Programming Through Cables

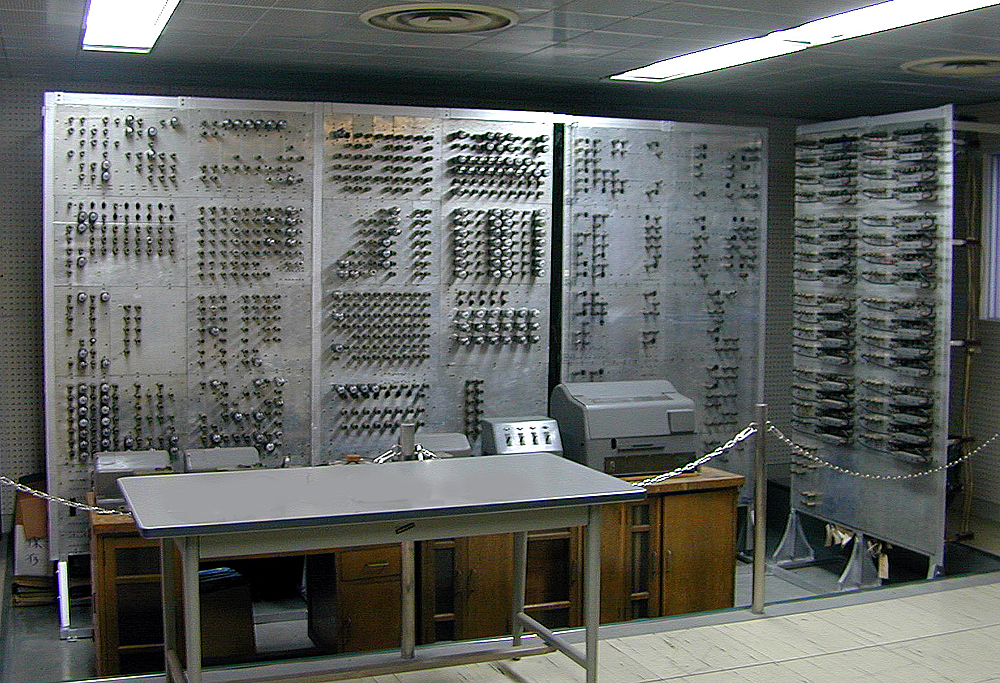

Despite its revolutionary speed, early versions of ENIAC had a significant architectural constraint that severely hampered its versatility: programming was done physically. To reprogram the machine for a new task—whether changing the type of ballistic calculation or switching to a different mathematical function—engineers had to manually rewire thousands of cables and toggle switches on its numerous panels. This was an extremely laborious and time-consuming process that, depending on the complexity of the task, could take several days, sometimes even a week.

Essentially, the operator had to literally “re-plug” parts of the apparatus, physically changing its internal logic. This limitation clearly reflected its original purpose as a giant electronic calculator designed to solve one specific type of military problem, rather than a general-purpose device in the modern sense. The machine was fast, but its preparation for work was cumbersome and slow.

This serious bottleneck, which contradicted the idea of a universal computer, was only resolved later. Significant modifications introduced in 1948 allowed for the partial storage of programs in memory, which greatly simplified the process and transformed ENIAC into a more flexible and intellectually autonomous device. This transition from physical to software coding was a pivotal step in the evolution of all computer architecture.

The Legacy

Although ENIAC was commissioned by the Army during the war, it was officially unveiled only on February 15, 1946, after the cessation of hostilities. Thus, its direct impact on the course of World War II was minimal. Nevertheless, its post-war activity proved decisive.

In the post-war period, the supercomputer was used for various critical calculations:

- Atomic Research. Computations related to the development of thermonuclear weapons.

- Scientific Tasks. Cosmic ray studies and weather forecasting.

- Ballistic Calculations. Continuing work for the Aberdeen Proving Ground military laboratory.

ENIAC laid the theoretical and engineering groundwork for the next generation of computers, including EDVAC and UNIVAC, which already featured internal program storage. The invention by Eckert and Mauchly became the starting point of the digital age.

Technological Fragility

The engineering brilliance of ENIAC was accompanied by a series of significant technical challenges, particularly concerning its daily operation. Due to the use of nearly 18,000 vacuum tubes—the core computational elements—the machine was extremely sensitive to strain.

The main issue was reliability. Electronic tubes, operating at high power, regularly burned out. Statistics indicate that, on average, one component failed approximately once a day, requiring an immediate halt to operations.

Finding a faulty tube within the enormous complex, which occupied 1,800 sq ft (1.67 a) and generated substantial heat, was a difficult and lengthy process.

- The technical staff had to quickly locate and replace defective components to minimize downtime.

- Over time, the maintenance team achieved remarkable proficiency, reducing the time to locate and replace a fault to as little as 15 minutes—a true feat under the circumstances.

Thus, the engineers had to contend not only with ballistic equations but also with the constant electrical and thermal instability of this first electronic giant.

The Computing Giant: Key Facts

| Feature | Value | Additional Detail |

| Development Location | University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. | Moore School of Electrical Engineering. |

| Principal Inventors | John Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert. | Received contract from the U.S. Army. |

| Number of Vacuum Tubes | Approximately 18,000 units. | High count enabled its speed. |

| Official Launch Date | February 15, 1946. | After the end of World War II. |

| Computational Speed | Up to 5,000 additions per second. | Thousands of times faster than electromechanical devices. |

| Weight | 30 tons. | Required special infrastructure and maintenance. |

ENIAC became more than just a machine; it was a manifesto for the electronic era. It proved that computations previously taking weeks could be executed in mere seconds using purely electronic components. This tube-based giant from the City of Brotherly Love, despite its cost and complex maintenance (primarily due to the regular failure of vacuum tubes), finally ended the era of mechanical calculators. It pioneered a new industry, inspired the Von Neumann architecture, and directly influenced the invention of commercial computers like UNIVAC.

Therefore, ENIAC is not merely a historical artifact, but the undeniable father of all modern digital technologies that we use today.