Philadelphia, renowned as the cradle of American democracy and industrial thought, also became the birthplace of organized savings for ordinary citizens. At a time when financial institutions primarily served wealthy merchants and speculators, it was in this city that the idea emerged that even the smallest sum had the right to grow. The founding of the Philadelphia Saving Fund Society (PSFS) in 1816 was not just the opening of a bank; it was a genuine social innovation that transformed the nation’s financial habits. Read more about it at philadelphia.name.

Following the European Example

In the early 19th century, the United States suffered from a significant financial gap and an urgent need for financial inclusion. At the time, there were virtually no institutions that offered secure money storage for the vast majority of the population: laborers, artisans, and domestic servants.

The commercial banks that dominated the scene were not interested in handling small deposits, as the profitability of servicing large trade operations and wealthy clients was significantly higher. Consequently, the general availability of financial services was essentially nonexistent, leaving the “modest classes” without a reliable place to store their savings. People were forced to keep their money at home, which was risky and earned no income.

The idea of creating a specialized institution—a savings bank—came to Philadelphia from Europe, specifically from Great Britain, where similar institutions successfully functioned as part of social reforms. A group of influential Philadelphia citizens, led by Condy Raguet—a successful merchant and diplomat—decided that establishing a fund for residents of all means was not just an economic concern but a matter of social justice and moral upliftment. They were convinced that saving was the key to financial stability, personal self-sufficiency, and reducing citizens’ dependence on charity. This conviction led to the founding of The Philadelphia Savings Fund Society.

The First Deposit

A historic event took place on December 20, 1816. This was the official founding date of the aforementioned institution. PSFS became the first savings bank in the United States.

The first officially documented depositor was an African American servant in the home of founder Condy Raguet. This fact clearly demonstrates the society’s initial mission: to serve those ignored by the larger financial system. The society limited the size of individual deposits to ensure the institution truly focused on the needs of working-class people, not the investments of the wealthy.

Humble Beginnings

The early years of PSFS were marked by deep volunteerism and civic responsibility. The institution operated entirely on the enthusiasm of its staff. Directors and management received no salary, performing their duties on a free basis. They would meet only a few times a month at the building of the American Philosophical Society—coincidentally founded by Benjamin Franklin—to personally accept deposits from laborers and servants.

This was a conscious non-banking approach based on trust and a community mission, not the pursuit of profit. This transparent and ethical model quickly earned the confidence of ordinary people who previously had no access to secure financial services.

Financial Success and Stability

The popularity of PSFS, as the first savings institution in the U.S., grew rapidly, demonstrating its significant contribution to developing a culture of savings.

- By 1850, the society had over 10,000 depositors—mostly working-class people and city employees.

- The total volume of deposits exceeded $1.7 million, significantly more than the national average for savings institutions.

Key evidence of its success was its extraordinary resilience. PSFS successfully weathered the banking crisis of the 1840s, which led to the bankruptcy of most other financial houses in Philadelphia. Its stability was ensured by a conservative and reliable investment policy focused primarily on mortgage loans and government securities, rather than speculative trading. Thus, PSFS not only taught people to save but also demonstrated the institution’s reliability in times of crisis.

An Architectural Landmark

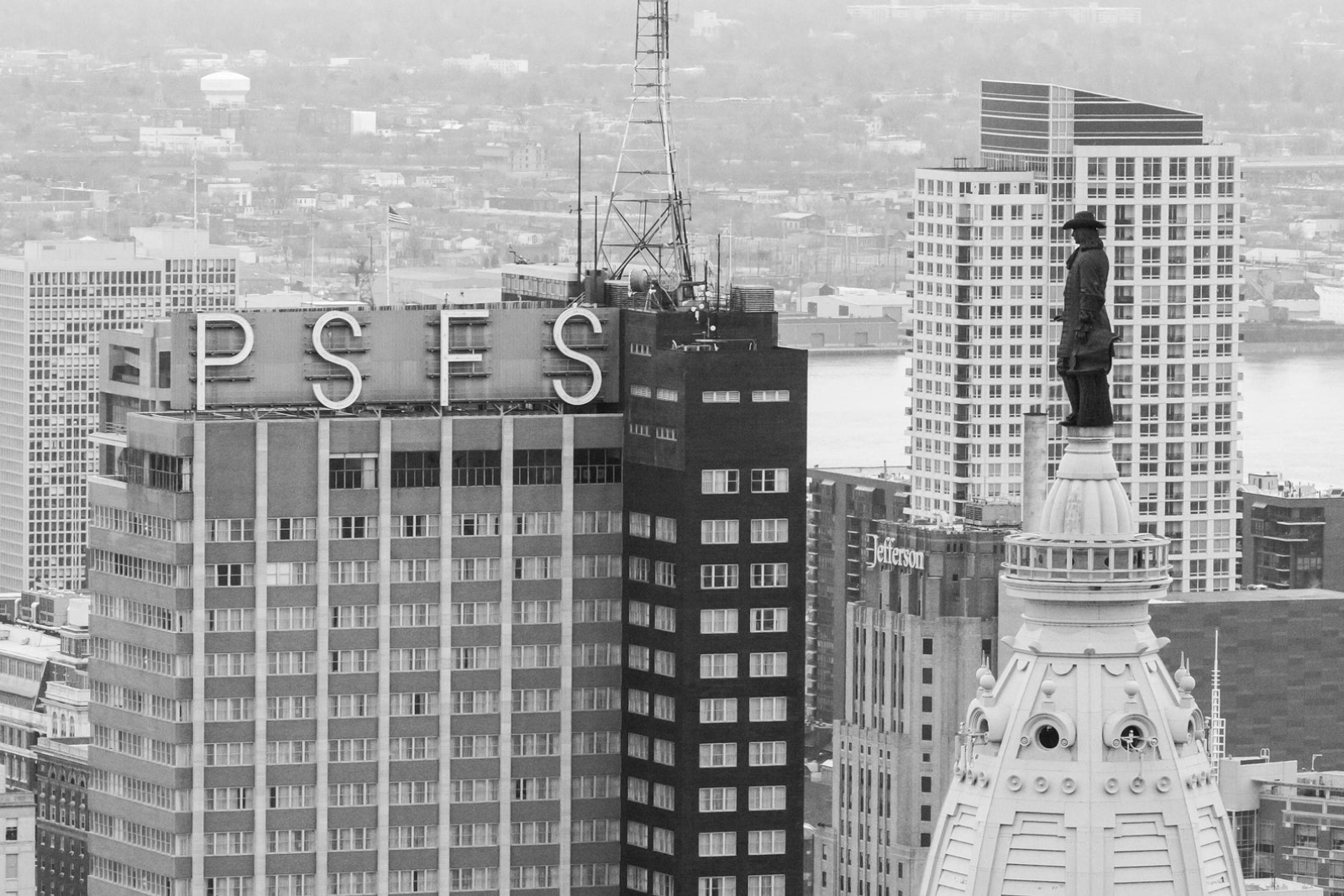

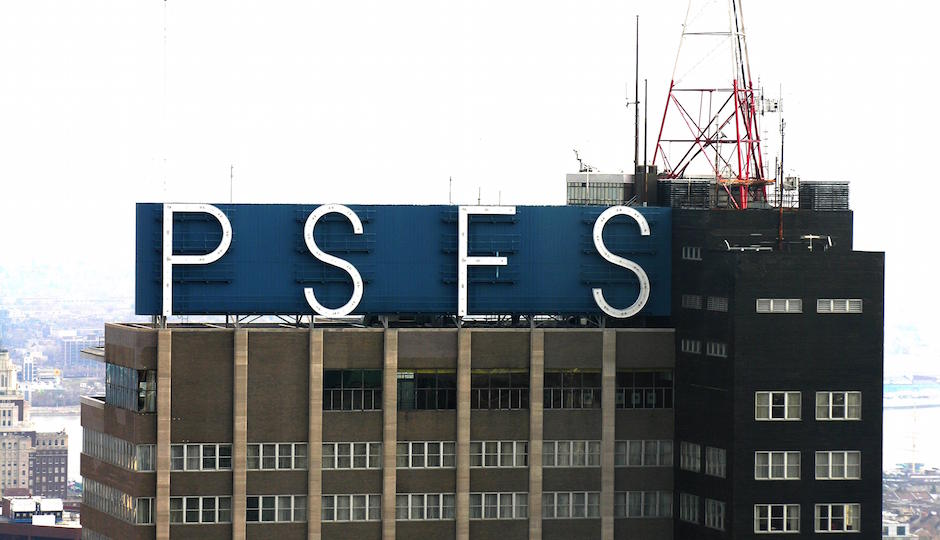

The reliability and financial growth of the Philadelphia Savings Fund Society reached their peak in the early 20th century, which was materialized in a monumental architectural project. In 1932, at the height of the Great Depression, PSFS moved into its famous headquarters—the PSFS Building skyscraper.

This 36-story building, designed by architects William Lescaze and George Howe, became a true architectural icon and a Philadelphia signature.

- First in the U.S.: The PSFS Building is considered the first skyscraper in the United States to be fully executed in the strict International Style (Modernism). Its design consciously rejected the classical decorative elements typical of American skyscrapers at the time in favor of clean lines, smooth surfaces, and functionality.

- Innovation and Functionality: The structure represented not only architectural progress but also technological superiority. The building was equipped with revolutionary features for the era, including central air conditioning—a first of its kind—and modern high-speed elevators.

The skyscraper became the tangible embodiment of PSFS’s financial stability during an economic crisis. The gigantic neon “PSFS” sign on the roof, done in a custom font and visible for miles, became a permanent and undeniable symbol of Philadelphia and the institution’s financial reliability. Opened during the deepest economic downturn, the building showed that PSFS was an unshakeable fortress of savings. No better advertising was needed.

The Changing of Eras

Despite more than a century and a half of impeccable reputation and its status as the first savings bank in the United States, the Philadelphia Saving Fund Society could not withstand the financial turbulence of the late 20th century. The era when savings institutions operated as stable, socially oriented non-profit organizations was coming to an end.

The crisis began in the 1970s and 1980s with the deregulation of the U.S. financial sector. Traditional savings institutions, which primarily earned revenue from fixed-rate mortgage loans, faced significant problems.

- Rising Inflation and Rates: The profitability of old loans decreased, while the interest rates they had to pay depositors increased.

- Aggressive Competition: New commercial banks and mutual funds began offering clients higher interest and new services.

To survive, the PSFS leadership made a risky decision: to transform the society. The institution began expanding into areas atypical for it, such as corporate finance and real estate investments.

Acknowledging its new, broader activities, PSFS changed its name to Meritor Financial Group in 1984. The goal was to emphasize the expansion of financial services. However, these new, high-risk projects led to significant multi-million dollar losses.

Ineffective risk management and major losses finally undermined the financial stability of the once unshakable organization. In December 1992, after a failed rescue attempt, the Philadelphia Saving Fund Society filed for bankruptcy. This event was the symbolic end of an era when saving was viewed as a civic virtue, not just a tool for making a profit.

The Sign That Survived

Despite the institution’s financial collapse, its Modernist headquarters, recognized as a national historic landmark, was given a new lease on life. In 2000, the tower was converted into the luxurious Loews Philadelphia Hotel.

A unique condition for preserving the architectural icon was the retention of the “PSFS” sign. This iconic lettering continues to glow over downtown Philadelphia. It serves as a silent reminder of the origins of American savings—born here—and of an important, albeit dramatically concluded, chapter in the nation’s financial history.